Village Needed: Adoption Program – A New Model of Indigenous Child Care

LA PLANT, South Dakota. Behind a gravel road lined with old white wooden buildings is an 8-acre new village dotted with colorful houses, wigwams and a thermae.

Simply Smiles Children’s Village in this small town on the Cheyenne River Reservation is home to a program to improve outcomes and reduce injuries for First Nations foster children.

All foster programs are aimed at the safe reunification of children with their families. Children’s Village goes further.

“We want to make Lakota citizens of the world,” said Colt Combellick, who oversees mental health programs in the village. “If we can help them re-learn their culture and their heritage and connect them to the resources they need to thrive, we will try to do that.”

The program is an example of a growing nationwide effort to improve services for Indigenous children after generations have been regularly traumatized by being separated from their families and cultures. While the era of Indian boarding schools has ended and improvements have been made to child welfare systems, indigenous families remain overrepresented in the foster care system.

The non-profit organization Simply Smiles aims to improve First Nations foster care by keeping children in their tribal community rather than placing them in off-reservation foster care. He hired trained professionals whose full-time job is taking care of children in rural areas, who provide cultural programs and mental health services.

“In fact, we have research that shows that children with stronger cultural identities have better outcomes for child well-being” such as school success and drug withdrawal, said Angelica Day, an associate professor at the University of Washington and an expert on protection of indigenous children. .

Day, not affiliated with Simply Smiles, said she was excited about any innovative program to improve the welfare of children in tribal communities as long as it provides adequate training so that foster parents can support children and avoid staff turnover. She said it is also important for organizations to have an independent assessment of children’s progress after they leave admissions programs.

It’s too early to tell if Simply Smiles will achieve its goals, but the Children’s Village has the backing of Cheyenne River Sioux leaders and is attracting interest and visits from First Nations officials across the country.

A member of the Cheyenne River Sioux suggested that the non-profit organization establish a foster village on the reservation after learning of a similar program the non-profit organization was running in Mexico. The tribal council voted in favor of the idea, and Simply Smiles has advisors, including child protection experts, elders, and other leaders of the Cheyenne River Sioux and other tribes.

The Simply Smiles model combines home life in a family setting with the resources of a more institutional setting, said Brian Nurnberger, president and founder of the Connecticut-based nonprofit.

In the Children’s Village in La Planta, one foster parent takes care of three teenagers. He employs other parents to fill his three houses, which together can accommodate up to six parents and 18 children.

The family has access to a counseling center and family visit, as well as a large blue barn that stores a bus, repair equipment, and new clothes that the kids can “buy”.

MarShondria Adams, 39, grew up with half-siblings who were placed in several foster families. Last year, she moved 300 miles from Sioux Falls, South Dakota’s largest city, to La Plante, population of 167, to become a foster mother at Children’s Village.

On a recent cold and foggy morning, Adams’s three foster teens made smoothies for breakfast at their navy blue house with a pink front door in the Children’s Village. Adams drove them to school and then returned home, where she did laundry and filled out paperwork for the state child protection department. Her plan after school was to cook dinner while the kids were playing sports on YouTube.

Being a traditional foster parent in Sioux Falls would be “a difference of day and night,” Adams said. She would not have local resources and staff to help her and the children with tasks ranging from fixing flat tires to finding a specialist who conducts a learning disability assessment.

“All these people around me support and help me,” Adams said. Traditional adoptive parents likely spend more time than she does on the phone with caregivers and looking for other resources, she said.

Program foster parents receive 70 more hours of training than the state requires, including training in Lakota culture. It also offers telemedicine therapy, evaluation, and medication management for foster parents, children, and biological parents. Combellick said mental health services use evidence-based methods based on trauma information and cultural practices.

The non-profit organization funds these services through donations, grants, and the government, which also refers prospective adoptive children to Simply Smiles.

Combellick, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux, is another Simply Smiles employee with a personal history of family separation.

His father was 6 years old when his mother went missing and was found dead on the reservation. Combellick’s father and his siblings were sent 80 miles to an Indian boarding school where they lived for about a year before being reunited with their family.

Combellick said his father developed PTSD at a boarding school where he faced corporal punishment and was not allowed to speak Lakota.

“That’s what fueled my passion. I just wanted to know about my family history and how to break these vicious cycles of oppression,” he said.

Combellick became a social worker and hoped to someday find a way to support his tribe directly.

“I went to Simply Smiles and boom! is about 300 yards from where my ancestors grew up,” he said.

Studies in the 1970s showed that states with large Native American populations took up to 35% of Native American children from their families. Often this was due to judgments of poverty and traditional parenting practices rather than abuse. Of those who ended up in foster families, 85% were placed with non-indigenous families.

One of the children’s rooms at the Simply Smiles Children’s Village home in La Planta, South Dakota. (Ariel Ziontz / KHN)

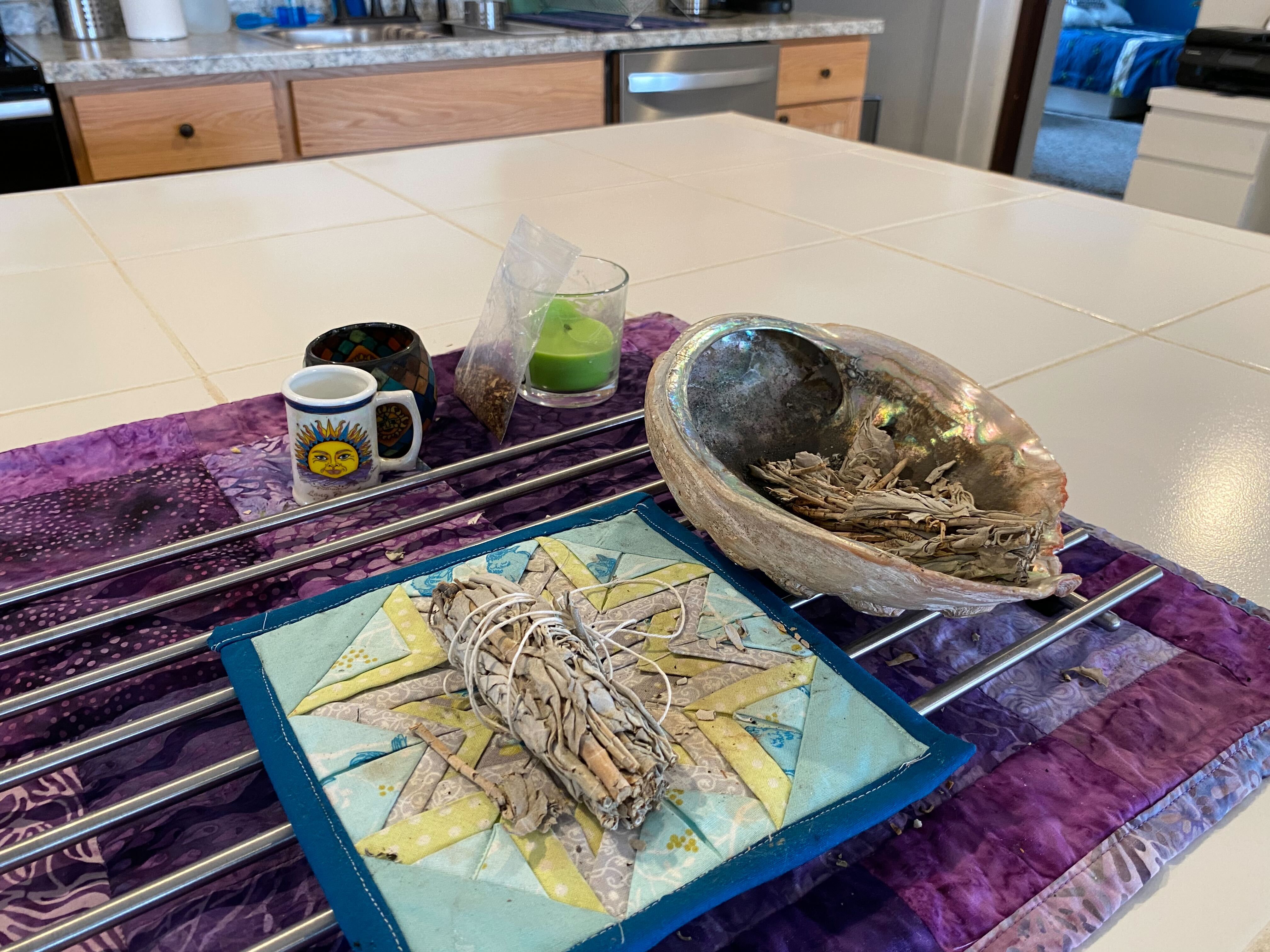

Bunches of dried sage lie on the kitchen table at a home in the Simply Smiles Children’s Village on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota. The Lakota use sage for purification rituals, medicine, and other uses. (Ariel Ziontz / KHN)

Congress passed the Indian Children’s Welfare Act in 1978 after hearing testimony about the psychological and cultural consequences of family separation. The law seeks to ensure that Native American families stay together or, when that is not possible, place children with relatives or other members of the tribe.

The future of India’s Child Protection Act is now in the hands of the Supreme Court. Critics challenging the law in court say it is racially discriminatory. Supporters say the act is backed by a long-standing but now threatened legal standard that holds tribes to be sovereign political entities.

Experts say the law has reduced disparities since the 1970s, but by 2003, child protection agencies were still more likely to investigate and substantiate allegations against Native American families than other groups, and take their children away more often than children of any other group. data analyzed by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

And as recently as 2020, Native American children were nearly three times more likely to be placed in foster care than other children, according to an analysis by the Casey Foundation. More than half of these adopted children were placed with non-indigenous relatives or guardians.

South Dakota, which has a 60% higher foster child rate than the national average, lacks licensed foster parents from all walks of life.

This level, and the shortage, is highest for native South Dakotas. More than half of the state’s adopted children are Native Americans, although First Nations children make up only 12% of the population.

South Dakota legislators recently rejected a bill that would have codified parts of India’s Child Welfare Act into state law. But they can set up a task force to study how the state can improve the well-being of indigenous children.

Eleven percent of the state’s licensed foster families are Native American, according to the state. Child welfare expert Day, a descendant of the Ho-Chunk people, said some Native Americans cannot or do not approve of foster children because they have low incomes or live in overcrowded or substandard housing.

“It doesn’t look like the tribal families don’t want to get involved and do the job. The thing is, we have barriers, systemic barriers built into the system that discriminate against families who want to do this job,” she said.

Even with pay and support in place, Simply Smiles had a hard time hiring and retaining caregivers. The first foster family arrived in the fall of 2020, but the parent burned out due to the closure of the reservation due to the pandemic. Another parent from a large city outside of South Dakota left, finding life in such a remote area too difficult.

Marcella Gilbert, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux, coordinates cultural programs such as powwow rides and elk and bison hunting trips. She also takes care of the children when their foster parents need a break.

“We are asking people to do the hardest job in the world – to be the parents of children who come to our homes with loss and trauma,” she said.

Dallas Press News – Latest News:

Dallas Local News || Fort Worth Local News | Texas State News || Crime and Safety News || National news || Business News || Health News

texasstandard.news contributed to this report.