Judge Fines California Every Day It Doesn’t Follow Prison Suicide Prevention Measures

A federal judge this week said she would begin fining California potentially tens of thousands of dollars a day after more than 200 inmates committed suicide in eight years in which state corrections officers failed to comply with court-ordered suicide prevention measures.

Addressing a chronic tragedy that has plagued the state for decades, Chief U.S. District Judge Kimberly Mueller said she will begin fining April 1, $1,000 a day for each of the 15 outstanding warranties, until all 34 adult prisons in the state are cleared. will fully comply with the requirements.

At the same time, it will impose penalties for the state’s failure to hire enough mental health professionals. And she set a hearing for August to recover more than $1.7 million in fines that have accumulated since 2017 under a previous ruling to punish delays in transferring prisoners to state mental hospitals.

“The court is at a critical crossroads,” Mueller wrote weeks before her ruling, which was released Tuesday. She said inmates with severe mental disorders make up more than one-third of California’s prison population of about 96,000 and have “waited too long for constitutionally adequate mental health care.”

Government officials said they would review the judge’s rulings. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokeswoman Vicki Waters said in a statement that “suicide prevention is a very important issue for us.”

In court documents, government officials objected to Mueller’s setting “an unworkable, near-impossible standard.” They pointed to a drop in suicide rates in each of the last two years after two decades of California consistently surpassing the national suicide rate for state prison systems. The 15 suicides in 2021 were the lowest in two decades and half the annual average for that period. Lawyers representing the prisoners say there were 19 suicide deaths last year, although the official report has yet to be released.

These recent lower suicide rates are “significant improvements and an absolute testament to success,” Paul Mello, an attorney representing the state, told Muller at a Feb. 10 hearing. Court-appointed suicide prevention expert Lindsey Hayes said the reasons for the sudden drop are unclear and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic will need to be analyzed.

Suicide in California prisons has long been considered a key indicator that the prison system is not providing adequate mental health care. Mueller’s predecessor ruled in a class action lawsuit 27 years ago that California provided prisoners with unconstitutionally poor mental health care. However, federal judges have struggled to make improvements despite repeated orders in the case.

This time around, Mueller is acting after Hayes found the branch was still substandard despite the 2015 order. Safeguards include things like suicide prevention education, suicide risk assessment, suicide-resistant cells, and checking vulnerable prisoners every 30 minutes, and often more often, to make sure they are not harming themselves.

“They are very standard in jails and prisons across the country and they don’t use them,” said Michael Biehn, one of the lawyers representing the prisoners.

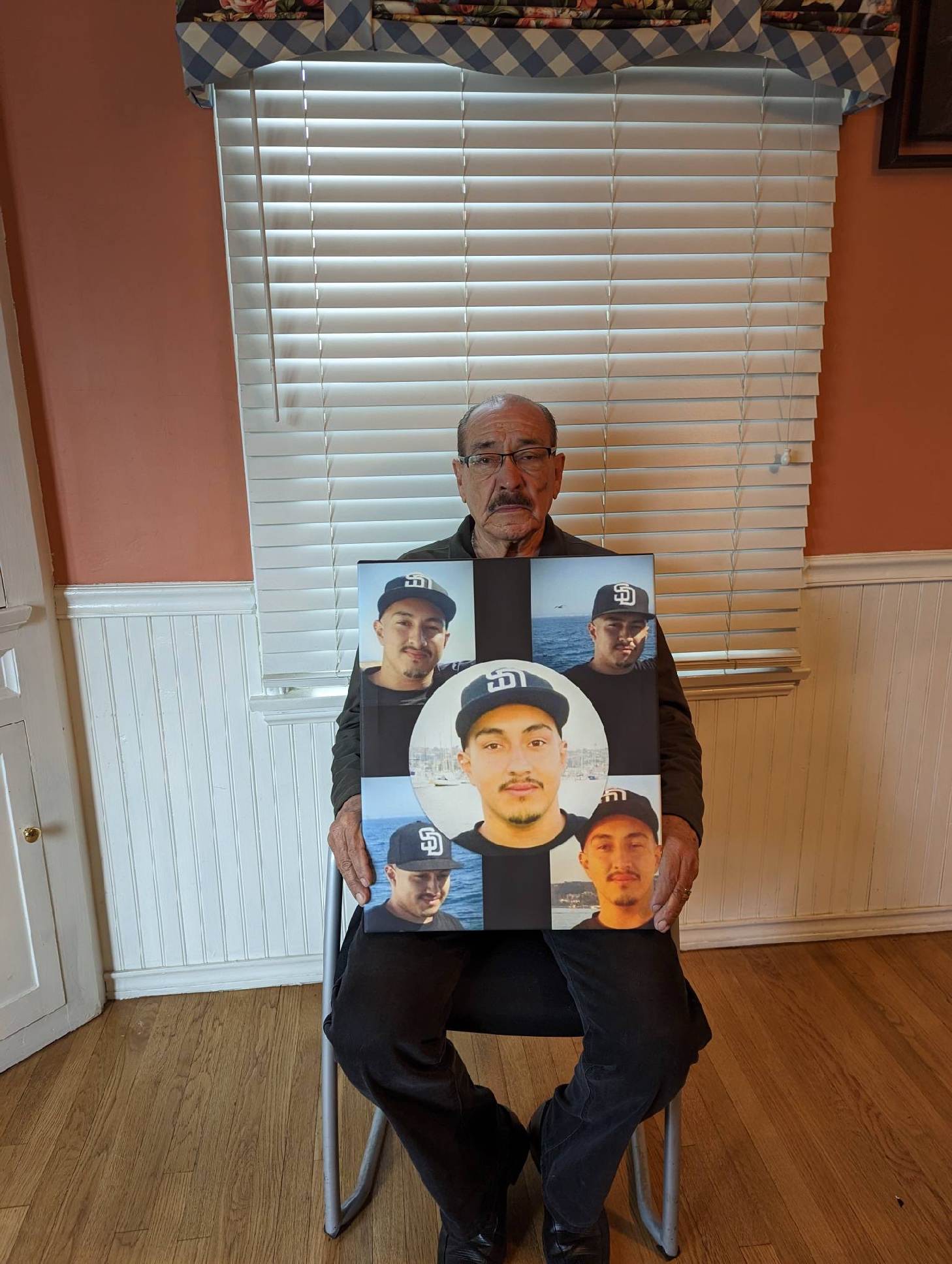

Among those who, according to correctional officers, committed suicide, is 31-year-old John Pantoia. According to the Sacramento County coroner, he died by hanging in June from a ligature torn from a bed sheet.

Pantoja was a funny, loving, caring, healthy, athletic young man until he entered the California juvenile justice system at the age of 16, his sister and father told KHN on Tuesday.

According to them, after five years he became a different person.

“He came out mentally just completely exhausted,” with multiple mental health diagnoses, including schizophrenia, and exhibiting mood swings consistent with bipolar disorder, Elizabeth Pantoia said. “Before entering, we did not see these signs. … It was the opposite of how we knew him.”

A few months after his release from juvenile prison in 2012, he was involved in a robbery and shootout with Chula Vista police. His defense at the time was that he tried to “commit suicide by the police” by enticing the officer to kill him. According to Amado Pantoh, one day in prison, John heard voices that he blamed on the mental illness treatment he was prescribed. Amado and Elizabeth said that John appeared to be looking forward to his family’s birthday visit and parole hearing in 2026, based on his young age at the time of the crime.

His mental health has indeed deteriorated over the past five years, they said, with him repeatedly placed in solitary confinement and denied family visits during the pandemic. More recently, the television he used as a form of therapy broke down, although his family sent him a new one and he saw healthcare workers complaining of chronic pain.

He died the next day with half a dozen drugs in his system, including drugs for depression, pain, and seizures.

In a report on prisoner suicides between January 2020 and April 2022, Hayes often detailed missed opportunities to prevent deaths:

- An inmate at the Sacramento County Maximum Security Prison committed suicide by stabbing his neck on Christmas Eve 2020, hours after he was seen drinking liquid detergent in his cell. Correctional officials said he also “behaved irrationally, was stressed, pacing back and forth, crying, getting frustrated after a string of phone calls with his family.” A crisis counselor spoke to him at the door of his cell because he refused to come out but denied that he was going to kill himself. The adviser asked no more questions, citing a lack of confidentiality, and a few hours later the prisoner committed suicide.

- An inmate at the Tehachapi State Prison was found hanging from a sheet vent in his cell on January 5, 2020. He has a long history of cuts to his wrists and other acts of self-destruction, including multiple times in the two days before his death. A few hours before the suicide, the consultant decided that it was not serious. But a subsequent check showed that his self-mutilation – along with his “bizarre statements and heightened paranoid delusions” – should have been warning enough. He left a note saying that he feared other inmates were plotting to kill him.

- The prisoner was found hanging from a sheet in his cell at the Corcoran Addiction Treatment Center the day before Thanksgiving 2021. His 11 years in prison were spent mostly in mental health programs for repeated cuts and hallucinations of voices saying people were trying to kill him. The entry in the medical record that he was seen by a consultant on the day of death “was falsified by the clinician.” The department’s review revealed a “disturbing pattern” where mental health providers said they would offer interventions but never did.

Mueller, who has been signaling for weeks that she will be imposing daily fines, said during a February hearing that they are needed to “enforce recommendations” after the state repeatedly missed deadlines to comply with nearly half of court-ordered safeguards.

“The court finds further delay in the full implementation of the necessary suicide prevention measures by the defendants unacceptable,” Muller wrote in her latest ruling.

Müller also ordered fines to be imposed for each unfilled position exceeding 10% of vacancies in the required number of mental health professionals needed to care for prisoners with serious mental disorders. These fines will be based on the maximum wage for each job, including those over or near $300,000 a year, and Mueller said she will set a hearing to find the state disrespectful and order payment if the fines accumulate over three months in a row. .

The state has been falling short of filling requirements for more than four years, Mueller said, noting that more than 400 positions are vacant across the state.

In 2017, Mueller imposed $1,000-a-day fines in an attempt to end a chronic backlog in sending prisoners to state mental institutions. She has never raised money, but has now scheduled an August hearing to do so.

Under her current order, fines will accumulate until Hayes determines the state is not in compliance. Once its review is completed — a process that previously took many months — Mueller said she will set a hearing on the payment of fines.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Foundation.

Dallas Press News – Latest News:

Dallas Local News || Fort Worth Local News | Texas State News || Crime and Safety News || National news || Business News || Health News